Alabama has 28,296 people in prison. We can reduce that number.

If Alabama were to follow these and other reforms in this Smart Justice 50-State Blueprint, 12,511 fewer people would be in prison in Alabama by 2025, saving nearly $470 million that could be invested in schools, services, and other resources that would strengthen communities.

Over the past five decades, the United States has dramatically increased its reliance on the criminal justice system as a way to respond to drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty. As a result, the United States today incarcerates more people, in both absolute numbers and per capita, than any other nation in the world. Millions of lives have been upended and families torn apart. This mass incarceration crisis has transformed American society, damaged families and communities, and wasted trillions of taxpayer dollars.

We all want to live in safe and healthy communities, and our criminal justice policies should be focused on the most effective approaches to achieving that goal. But the current system has failed us. It’s time for the United States to end its reliance on incarceration, invest instead in alternatives to prison and in approaches better designed to break the cycle of crime and recidivism, and help people rebuild their lives.

The ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice is committed to transforming our nation’s criminal justice system and building a new vision of safety and justice. The Campaign is dedicated to cutting the nation’s incarcerated population in half and combatting racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

To advance these goals, the Campaign partnered with the Urban Institute to conduct a two-year research project to analyze the kinds of changes needed to cut by half the number of people in prison in every state and reduce racial disparities in incarceration. In each state, Urban Institute researchers identified primary drivers of incarceration. They then predicted the impact of reducing prison admissions and length of stay on state prison populations, state budgets, and the racial disparity of those imprisoned.

The analysis was eye-opening.

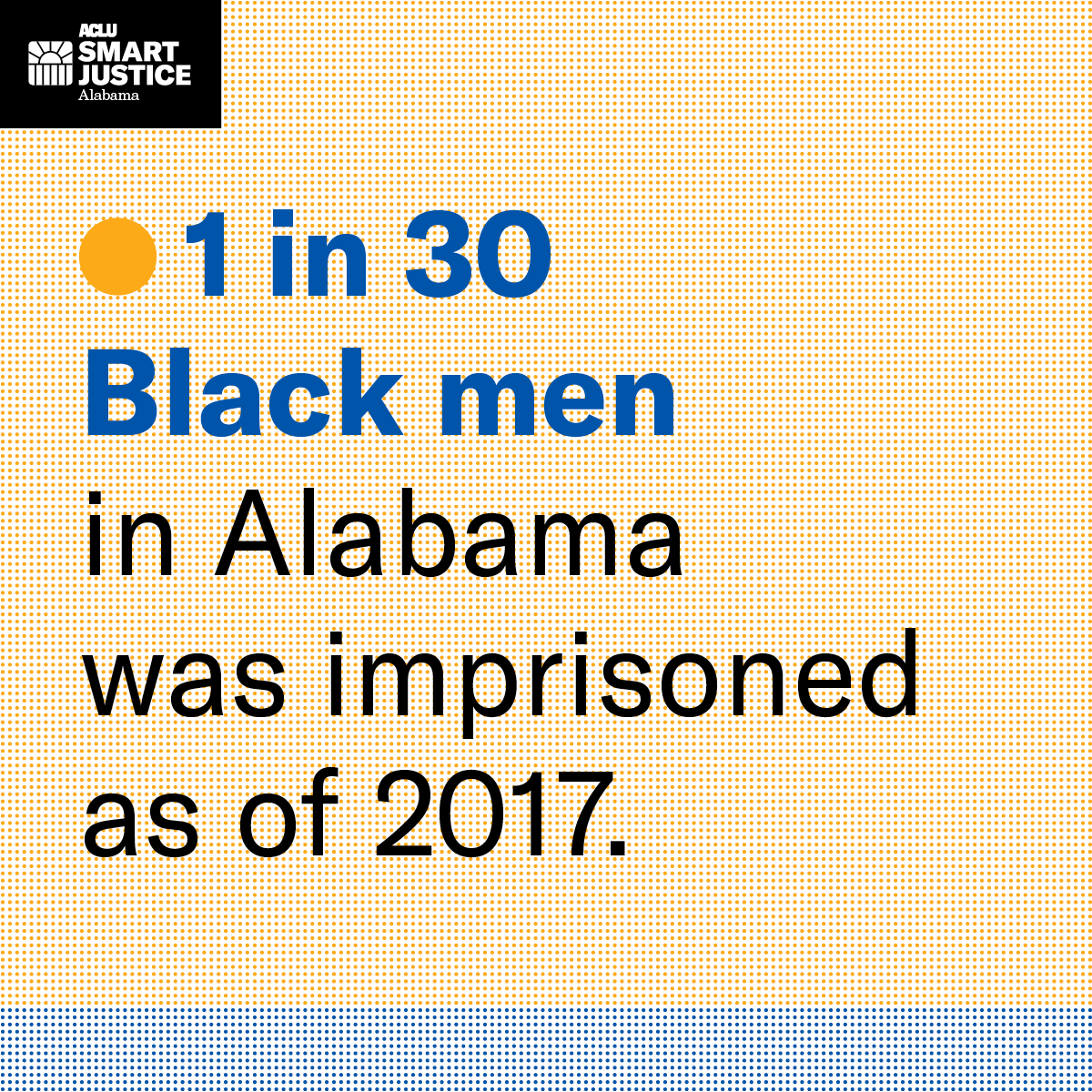

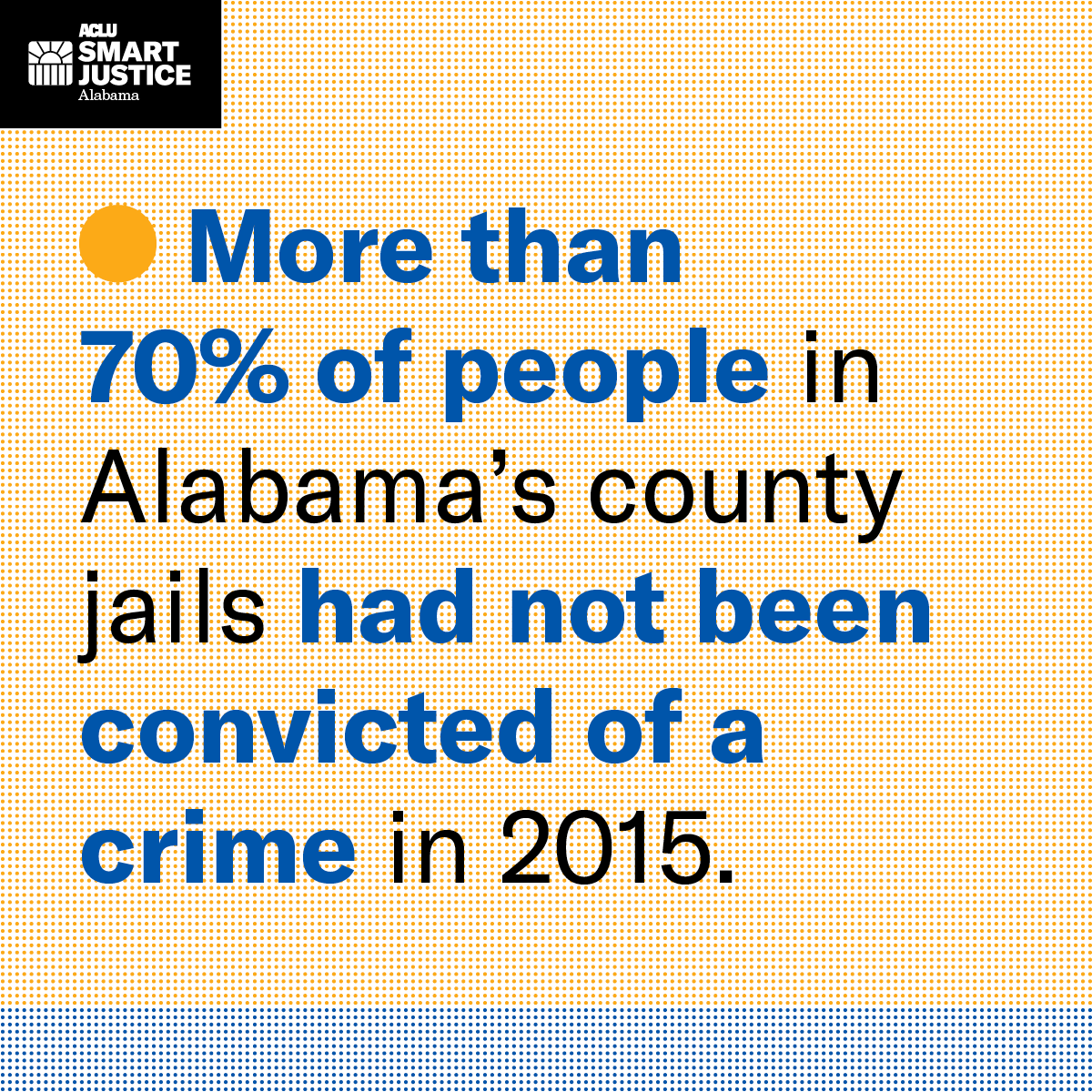

In every state, we found that reducing the prison population by itself does little to diminish racial disparities in incarceration — and in some cases would worsen them. In Alabama — where Black people represent 55 percent of the adult prison population despite constituting only 26 percent of the state’s adult population overall — reducing the number of people imprisoned will not on its own reduce racial disparities within the prison system. This finding confirms for the Campaign that urgent work remains for communities, policymakers, and criminal justice advocates in Alabama and across the nation to focus on efforts — like reducing incarceration before trial through bail reform, preventing the incarceration of people arrested on misdemeanor and low-level felony charges, and expanding parole opportunities — that are specific to combatting these disparities.

In Alabama, the incarcerated population has skyrocketed since 1980, growing fourfold as of 2016. This growth has bloated and strained those prisons, forcing them to operate at 164 percent of design capacity in 2017. Much of this growth has come as a result of prison sentences for drug offenses — in 2017, 34 percent of all system-wide admissions into Alabama’s prison system were for such offenses. More than one in five admissions were for drug possession that year, indicating that Alabama is in dire need of alternatives to incarceration for people convicted of drug offenses, including those in need of treatment and rehabilitation for addiction problems. Overall, more than one in three people incarcerated in Alabama’s state-run prisons in 2016 were serving time for a property or drug-related crime.

Contributing to the rise in Alabama’s prison population has been a series of sentencing enhancement laws that increase sentence severity for people who have prior felony convictions. Recent reforms have decreased the use of the “habitual offender enhancement” — the most severe of Alabama’s enhancement laws — but thousands of people who were sentenced under this law remain in prison. As of 2017, around half of people in Alabama’s prisons are serving a sentence of 20 years or more. For people with a history of substance use disorder, options are limited both in and outside of prison. Estimates indicate that 75 to 80 percent of people in Alabama’s prisons have a history of substance use.

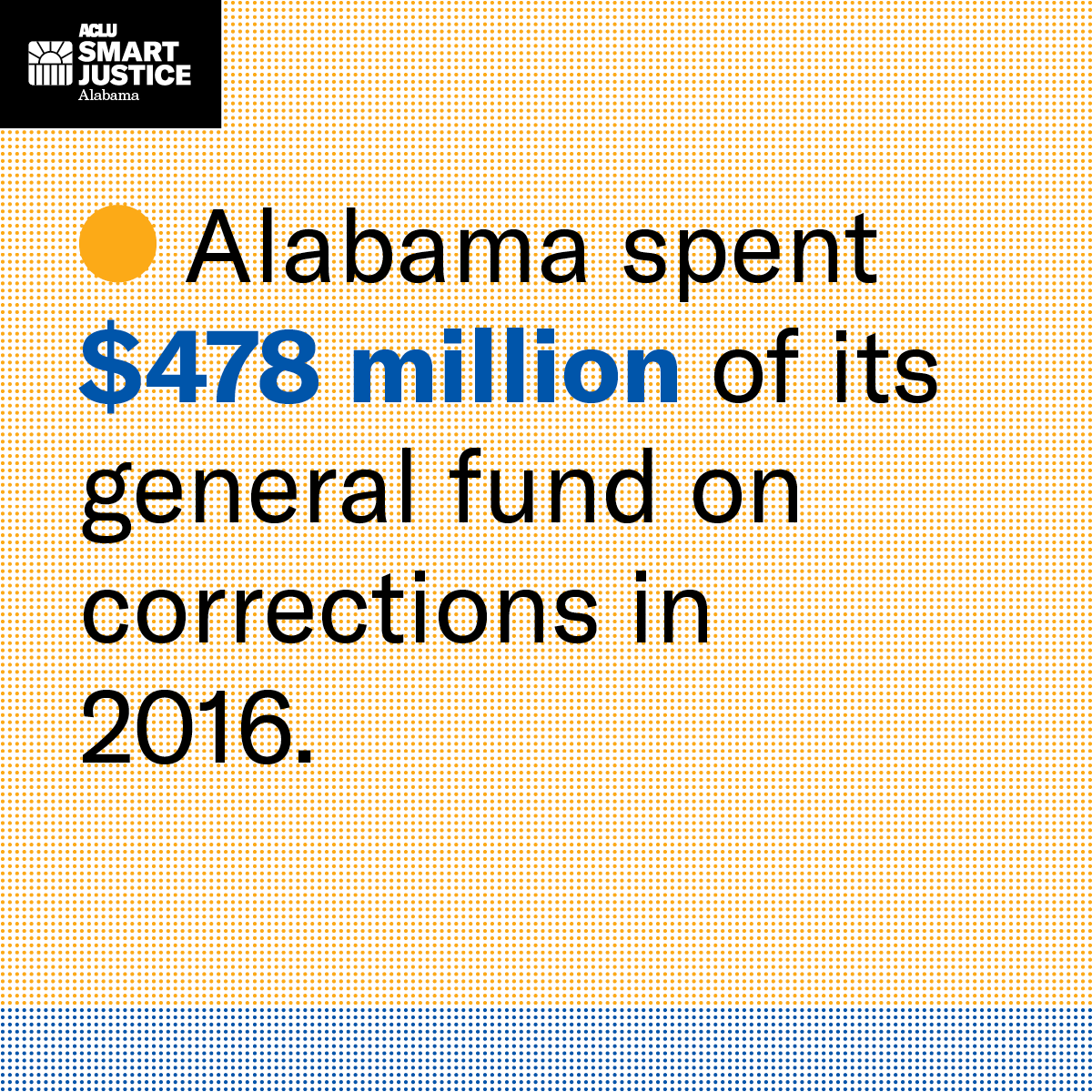

And all this is expensive. In 2016, Alabama spent $478 million — nearly half a billion dollars — of its general fund on corrections. Spending on other priorities, like education, has lagged behind the state’s high corrections spending.

So what’s the path forward?

Any meaningful effort to reach a 50 percent reduction in incarceration in Alabama must encourage prevention-oriented approaches to public safety, such as recognizing drug addiction as a public health problem. Rather than relying on jails and prisons, policymakers should implement evidence-based alternatives, like expanded treatment or mental health care programs, to help divert people to rehabilitative programs. Given Alabama’s high rate of prison admissions for drug possession and other drug offenses, reevaluating the use of incarceration to address drug abuse and distribution will be crucial in reducing the state’s bloated prison population. In addition, reducing sentencing ranges — especially for drug offenses, burglary, assault, robbery, and public order offenses like disorderly conduct — will lower costs and shrink the number of imprisoned Alabamians.

Alabama should also reform its juvenile justice system, which mandates that children who are 16 or older be automatically tried as adults for capital crimes as well as some felonies and drug offenses. Studies show that youths are more likely to recidivate when they are incarcerated with adults, and there is evidence that transfers of youth to the adult justice system exacerbate racial disparities. A plan to reduce the prison population must include extending juvenile jurisdiction at least through the age of 17 for all crimes, as well as ending fines and fees in the juvenile justice system, restricting the prevalence of out-of-home placements for juveniles, and preventing inappropriate arrests in Alabama schools.

In 2015, Alabama enacted justice reinvestment legislation, which in part sought to address low parole rates by training staff in decision-making practices. The reforms have paid dividends, increasing the number of people granted parole by 17 percentage points between 2015 and 2017 alone. But there is still more that can be done. Only half of the people whose applications were considered by the parole board were granted parole in 2017. More than one in five people in Alabama prisons that year were older than 50. If someone is eligible for parole and there is no overwhelming need to keep them imprisoned, the presumption should shift towards their release rather than continued and costly time in prison.

The next steps are ultimately up to Alabama’s voters, policymakers, communities, and criminal justice reform advocates as they move forward with the urgent work of ending the state’s obsession with mass incarceration.

Download full report

Related Issues

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.